Orchard Fields is regularly used by locals and visitors, and although it does have some impressive earthworks, most people would find it hard to know how Malton Roman Fort was laid out, read on to find out more.

When Petillius Cerialis first arrived in Malton it is most likely that he constructed a tented temporary camp of around 22 acres to accommodate the troops of the 9th legion. [See Malton blog: https://www.maltonmuseum.co.uk/2021/03/06/petillius-cerialis-and-the-brigantes/]

What is still visible today – in Orchard Fields – are the remains of the defences of an 8.5-acre fort that was originally built in timber at around AD 79 during the governorship of Agricola. It is strategically very well-placed affording extensive views over the Wolds, and, on a clear day, it is still possible to see Seamer Beacon (a probable Roman site) just west of Scarborough.

The timber fort would have had a 5-metre-high walkway and was surrounded by a single ditch. Twenty-five years later the ramparts were rebuilt in stone with new double ditches being dug further out from the walls while the original inner ditch was back filled.

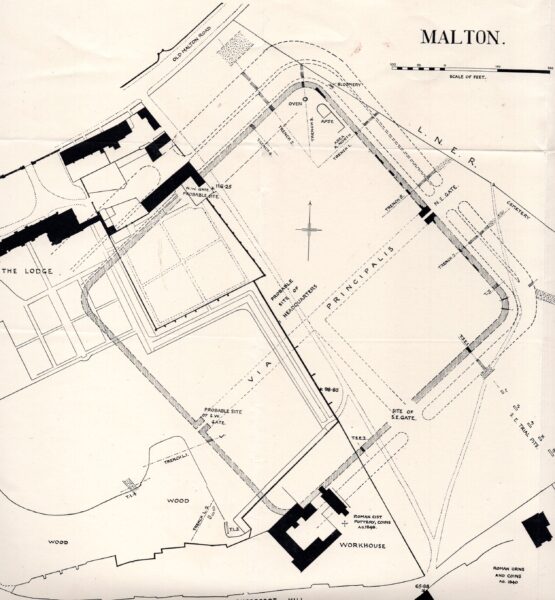

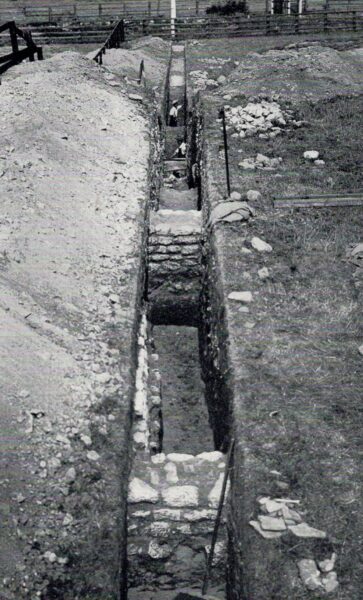

Figure 1 is a plan of Malton Roman Fort drawn by the archaeologist, Philip Corder, following his series of excavations in the 1920s. A contemporary photograph along trench 5 on the plan (Figure 2) clearly shows the stone north-east wall (in the centre of the picture) with the ditches further out towards the railway.

In common with most Roman forts Malton conformed to the classic playing card shape: a rectangle with rounded corners. It also had four entrances with the main gate (porta praetoria) being within the south-west rampart of the fort, enjoying road connections with York, Brough and Stamford Bridge. At the opposite side of the fort was the back gate (via decumana) leading to Hovingham and Whitby.

Two roads were central to the internal layout of any Roman fort. The via praetoria ran north-west from the main gate to join the via principalis in front of the headquarters building (principia). At either end of this were two further gates – the porta principalis sinistra and the porta principalis dextra – leading to Scarborough/Filey and York/Aldborough respectively.

The porta principalis sinistra (North-East Gate) was carefully excavated by Philip Corder in the 1920s. Originally it was a double portal wooden structure similar to the modern example that can be viewed at Lunt (Nr Coventry) (Figure 3). When the fort walls were rebuilt in stone this entrance was reformed as single inner and outer arches accommodating a central chamber flanked by two guard rooms. A good reconstruction showing what the first stone structure might have looked like can be seen at Cardiff Castle (Figure 4). Subsequently this gate went through several further modifications possibly including repairs by the rebel Emperor Carausius. [See Malton blog: https://www.maltonmuseum.co.uk/2021/01/11/carausius/ ]

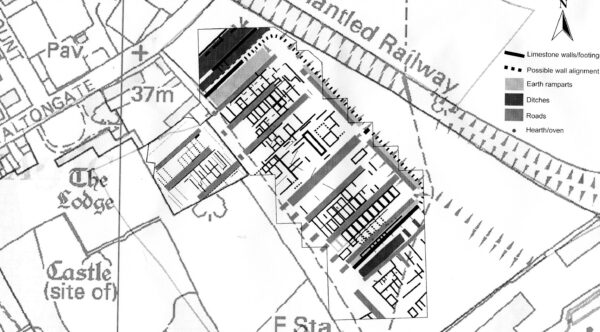

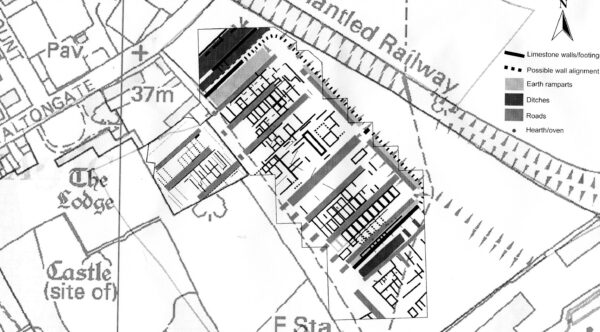

To date little digging has taken place inside the fort but geophysical surveys have identified probable barrack blocks, workshops, stores and granaries in addition to the principia (Figure 5). However, some limited excavations just inside the north-east wall of the fort in the 1920s found an oven and a late Roman building with an apse (Figure 6). Whether this apsidal structure was a domestic building, a public building or an early church remains uncertain.

For more information and guided tours around Orchard Fields please check out the Malton Museum website:

https://www.maltonmuseum.co.uk/online-booking/

Find out how to find Malton Roman Fort from:

Historic England and Ancient Monuments

Figure 1: Philip Corder`s 1920s plan of Malton Fort based on his excavations

Figure 2: Trench 5 looking north-east showing the stone north-east wall (in the centre of the picture) with the ditches (marked by the three men) further out towards to railway ©Malton Museum

Figure 3: Reconstructed wooden gate at Lunt ©Creative Commons

Figure 4: The North Gate of Cardiff Castle reconstructed in Roman style ©Creative Commons

Figure 5: Interpretation of geophysical survey data from Malton Fort ©TJ Horsley

Figure 6: Apsidal building (A), showing earlier rectangular building (B) beneath ©Malton Museum